20.109(S08):Transcript-level analysis (Day5)

Contents

Introduction

There are several ways to assess the presence or concentration of a protein. In the previous module, you used a colorimetric Coomassie-based assay to measure the concentration of protein expressed by your bacteria. Because you were purifying a His-tagged protein from bacteria induced primarily to express said protein, you could assume that the protein concentration that you measured was primarily inverse pericam. In contrast, today you are trying to measure the concentration of a specific protein that is only one among many in a complex mixture.

A great way to identify proteins is to exploit antibodies – also called immunoglobulins – whether in a Western blot or by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay). In native physiological settings (such as your own body), antibodies are secreted by B cells in response to pathogens. A given antibody is highly specific ($ K_D $ ~ nM) for its binding partner, called an antigen, and the entire antibody population for a given person is incredibly diverse (>107 unique antibodies). Diversity is maintained by recombination processes at the DNA level, and specificity entailed by protein structure.

Antibody proteins comprise constant (C) and variable (V) regions, on both their heavy and light chains. The C regions determine antibody effector functions, such as antibody-dependent killing of infected cells. The three hypervariable portions of the V region together make up the antigen-recognition site. Only a small portion of an antigen, called an epitope, is recognized by its cognate antibody. This ~10 amino acid region may be linear, or it may be made up of linearly distant regions and thus recognized only when the antigen is in its native conformation. For example, conformation-dependent antibodies are useful for distinguishing different collagen types.

Antibodies can be raised in animals, special cell lines, and even genetically engineered. Polyclonal antibodies (pools of antibodies that recognize distinct epitopes on the same antigen) can be obtained from animal serum. The animal is infected with the antigen of interest in the presence of a costimulatory signal, usually multiple times, and then bled. In this case, a large fraction of the antibodies obtained will not be against the antigen of interest. In contrast, monoclonal antibodies can be made both highly specific and pure. In this process, normal antibody-producing B cells are fused with immortalized B cells derived from myelomas, and the two cell types are fused by chemical treatment with a limited efficiency. To select only heterogeneously fused cells, the cultures are maintained in medium in which myeloma cells alone cannot survive (often HAT medium). Normal B cells will naturally die out over time with no intervention, so ultimately only the fused cells, called hybridomas, remain. Genetic engineering can be used to combine a human antibody ‘frame’ (all of the C and part of the V region) with an antigen-recognition site discovered in another species (e.g., murine). When antibodies are used as therapeutics, this decreases the possibility that the patient’s body will treat them as foreign, compared to an antibody produced from only mouse genes. Normally, injecting an antibody from species X into an animal of species Y will cause production of anti-X antibodies, called secondary antibodies. These can be very useful in technical assays, as you will see below.

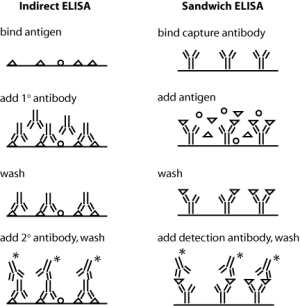

Today you will use antibodies against collagen in an indirect ELISA assay. Both indirect and sandwich ELISA are shown in the figure at right – can you see why sandwich ELISA might be the superior assay with respect to sensitivity and specificity? In indirect ELISA, the first step is to bind protein extracts, obtained from your three different culture conditions, to well plates. Next you will add a primary antibody that recognizes a particular antigen – namely, epitopes on collagen I or collagen II – to the relevant wells. Next, any excess antibody must be washed away with a mild detergent. Finally, a secondary antibody – namely one that recognizes the primary antibody – must be added. The secondary antibody is conjugated to alkaline phosphatase, which will undergo a colorimetric reaction in the presence of its substrate. Thus, the relative quantity of protein can be assessed by absorbance spectroscopy following substrate addition. To quantify the absolute amount of protein, you will run dilutions of a collagen standard in parallel with your culture samples. During your ELISA incubation steps, you can run the cDNAs you prepared last time out on a gel, and begin some analysis.

Reference: Abbas, A.K. & Lichtman, A.H. (2005). Cellular and Molecular Immunology (5th ed.). Philedelphia: Elsevier Saunders.

Protocols

Part 1: Day 1 of ELISA

We will run this assay in a 96-well microtiter plate, as we did for the fluorescence titration curves in Module 2. In ELISA, we will be testing for absorbance at a particular wavelength, rather than emission.

- Label one 96-well plate as your collagen I assay, and one as your collagen II assay. (Why might we want to use separate plates?)

- The first step in indirect ELISA is to adsorb all your samples to the wells. You will also need to prepare standard samples in the same plate, which get treated just the same as your test samples. These standards will be used as a reference for protein concentration. Both standards and unknown samples will be run in duplicate (see figure at right).

File:20.109-S08 ELISA plan.tiff

- You will be given 250 μL aliquots of collagens I and II at 10 μg/mL each. Prepare your standards as follows:

- Ultimately, you want to pipet 50 μL per well of each standard concentration, two wells per standard.

- Option 1:

- Prepare 7 eppendorf tubes with 120 μL of PBS each.

- Add 120 μL of the 10 μg/mL collagen to the first eppendorf tube, and vortex.

- Now take 120 μL of that standard (now 5 μg/mL) and add it to the next eppendorf tube.

- When you are all done or as you go, pipet the standards into the appropriate wells.

- Option 2:

- Pipet 50 μL of PBS into wells 1 and 2 of rows B-H (skip A!).

- Pipet 100 μL of the 10 μg/mL collagen into the appropriate wells (A1 and A2).

- Using a regular or multichannel pipet, transfer 50 μL of these solutions to the next wells down (B1 and B2), and mix with the PBS.

- Repeat, now moving 50 μL of the 5 μg/mL solution in the B wells down to the C wells.

- Either of these methods is called making doubling dilutions. Which way do you think introduces less error?

- Now add 50 μL of your samples to the appropriate wells. For the blank wells you should add PBS.

- Cover each plate (CN I and CNII) when you are done , wrap around it with parafilm to better prevent evaporation, and allow the samples to sit for 80 minutes. In the meantime, set up your agarose gel (Part 2).

- After the incubation time has passed, you will wash and then block your plate.

- First, flick the solutions in the plate into the sink.

- Using the multichannel pipet and a reservoir, add 200 μL of Wash Buffer to each well, then gently swirl the plate (by hand) for a few seconds.

- Flick the solutions out again, and then blot the plate against paper towels. You can smack the plates pretty hard, but it is possible to break them!

- Repeat the wash one more time.

- Finally, add 200 μL of Block Buffer to the plate. Wait another 60-90 minutes. In the meantime, work on your analysis (Part 3).

- Repeat the wash step that you performed above, again with two rinses.

- When you are ready, ask the teaching faculty for some primary anti-collagen antibodies (these should be diluted at the last minute). Add 100 μL of diluted antibody per well.

- Your samples will be left overnight in antibody solution, then moved back to block buffer by the teaching faculty.

Part 2: Agarose gel of PCR fragments

- Today we will run a 1.2% agarose gel. (Why do you think we would use a higher concentration of agarose than for the samples in Module 1?)

- Prepare enough diluted loading solution for 9 samples: 2 μL loading dye + 15 μL sterile water per sample.

- Mix 5 μL of each PCR product with 17 μL of diluted loading solution.

- Load your samples according to the following table, being very careful to load the same amount in each well:

| Lane | Collagen type | Sample | Volume to load (μL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N/A | 100 bp ladder | 11 |

| 2 | CN I | 2D cult. | 18 |

| 3 | CN I | 3D cult. 1 | 18 |

| 4 | CN I | 3D cult. 2 | 18 |

| 5 | CN II | 2D cult. | 18 |

| 6 | CN II | 3D cult. 1 | 18 |

| 7 | CN II | 3D cult. 2 | 18 |

| 8 | CN I | control rxn. | 18 |

| 9 | CN II | control rxn. | 18 |

- The samples will be run for ~ 45 min at 125V. The teaching faculty will then assist you in getting pictures with as high contrast as possible, then scan the pictures for analysis. (The digital photos will be immediately transferred to your laptops on a flash drive, and they will also eventually be posted on the wiki.)

Part 3: Begin ImageJ Analysis

Today you will use an image analysis program called ImageJ. This is offered free of charge by the NIH (National Institutes of Health). Your goal is to determine the collagen II: collagen I cDNA ratio for each of your samples, based on the intensity of the bands. This is one piece of evidence for the overall question posed by this module, namely, what factors affect chondrocyte phenotype maintenance (vs. de-differentiation to fibroblasts), and to what extent? If you finish the transcript-level analysis, you can move on to quantifying your live/dead data.

Transcript intensity

- Open your agarose gel image by selecting File → Open

- Using the rectangle tool, select an area in the background of the gel, the hit ctrl-M to measure it. Copy the mean and max intensity to an Excel file, and save the file.

- Now select each of your collagen bands in turn and repeat the process. Ultimately, you would like to compare the intensity of the CNII to the CNI band for each sample in an equivalent way. You have a lot of choices to make at this point, and there is no single right way to analyze your data.

- As one option, you could select equal areas from the center of each band, to avoid edge effects (where the band is dim) on mean intensity.

- On the other hand, if both bands are equally bright, a thicker band would be indicative of more DNA. So you might want to compare both areas and intensities, instead of just intensities. It’s up to you. Just try to make a good case for what you are doing.

- However, there are certain best practices for taking a ratio. For example, you probably want to subtract the background intensity from each sample band value.

- If you have time, you can explore the built-in gel analysis program in ImageJ.

Cell viability

Your goal for this section will be to compare the effort required for, and the resulting accuracy of, manually counting live and dead cells vs. doing so by semi-automated image analysis. After you are done, you might consider under what conditions you might prefer one method or the other.

If you don't have many cells to look at, extra data is available on today's talk page.

- Open your live cell image (green filter) by selecting File → Open

- Choose the line tool, and draw a line across the diameter of a typical cell

- Select Analyze → Set Scale, and put 10 μm in under Known Distance

- or get actual info from camera if possible

- Convert your image to grey scale using Image → Type → 8-bit

- Now you must somehow select your cells out from the background

- One way to do this is by choosing Process → Binary → Make Binary. However, you might find that clusters of cells are ‘read’ as a single cell.

- An improved method is to use Image → Adjust → Threshold. You can set the upper- and lower-bound intensities that define objects in your image. Play with the intensity sliders until your cells are mostly filled in with a red colour, but not overlapping with other cells whenever possible.

- Now you can count the objects. Choose Analyze → Analyze Particles, and select Show →Outlines, Display Results, Summarize, and Record Stats. Also choose a reasonable area (not diameter!) range for objects that are cell-sized.

- Try to play around with this process for a bit – are there any further changes you can make so the automated algorithm is as good as your eye?

- Record your final results (manual and/or best automated) in your notebook, for each sample that you have data for. Don’t forget to also count the dead cells, and subtract this number from the live cells (since the red colour usually bleeds into the green channel).

For next time

- For next time, complete a final draft of your essay on standards in the tissue engineering community (or other approved topic). Do your best to incorporate suggestions from the peer and faculty review.

- Keep thinking about your research proposal idea and its presentation as well!