Optics Bootcamp

Overview

You are going to build a microscope next week. The goal of the Optics Bootcamp exercise is to make that seem like a less intimidating task. The bootcamp mixes a little bit of mens and a little bit manus. It starts with a few written problems, followed by some exercises in the lab. The written problems will help you with the lab work. After you do the problems, come on by the lab. (Or do the problems in lab if you would like some help.) You will build an imaging apparatus made from some of the same optical components you will use in the microscopy lab, including an LED illuminator, an object with precisely spaced markings, a lens, and a CCD camera. You will compare measurements of object distance, image distance, and magnification to the values predicted by the lens makers' formula that was covered in class.

Problems

Problem 1: Snell's law

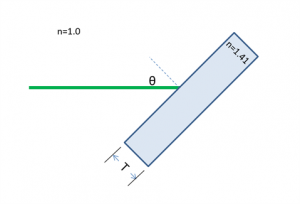

A laser beam shines on to a rectangular piece of glass of thickness $ T $ at an angle $ \theta $ of 45° from the surface normal, as shown in the diagram below. The index of refraction of the glass, ng, is 1.41 ≈√2. The index of refraction for air is 1.00.

(a) At what angle does the beam emerge from the back of the glass?

(b) When the beam emerges, in what direction (up or down) is it displaced?

Optional:

(c) By how much will the beam be displaced from its original axis of propagation?

Problem 2: chelonian size estimation

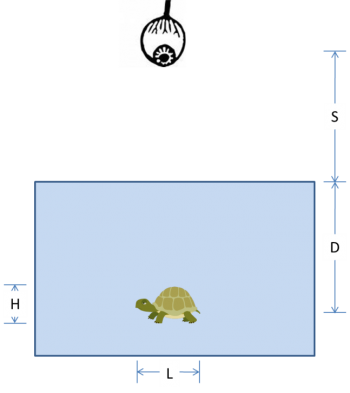

In the diagram below, an observer at height $ S $ above the surface of the water looks straight down at a turtle swimming in a pool. The turtle has length $ L $, height $ H $, and swims at depth $ D $.

(a) Use ray tracing to locate the image of the turtle. Show your work.

(b) Is the image real or virtual?

(c) Is the image of the turtle deeper, shallower, or the same depth as its true depth, $ D $?

(d) Is the image of the turtle longer, shorter, or the same length as its true length, $ L $?

(e) Is the image of the turtle taller, squatter, or the same height as its true height, $ H $?

Problem 3: ray tracing with thin, ideal lenses

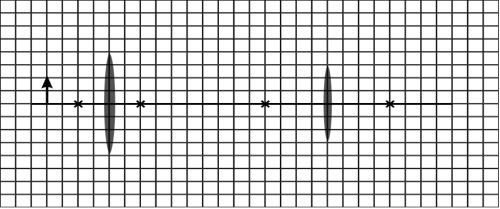

Lenses L1 and L2 have focal lengths of f1 = 1 cm and f2 = 2 cm. The distance between the two lenses is 7 cm. Assume that the lenses are thin. The diagram is drawn to scale. (The gridlines are spaced at 0.5 cm.) Note: Feel free to print out this diagram so you can trace the rays directly onto it. Or maybe use one of those fancy tablet thingies that the kids seem to like so much these days.

(a) Use ray tracing to determine the location of the image. Indicate the location on the diagram.

(b) Is the image upright or inverted? Is the image real or virtual?

(c) What is the magnification of this system?

Optional:

(d) Lens L1 is made of BK7 glass with a refractive index n1 of 1.5. Lens L2 is made of fluorite glass with a refractive index n2 of 1.4. Compute the focal lengths of L1 and L2 if they are submerged in microscope oil (refractive index no = 1.5).

Problem 4: this will be really useful later

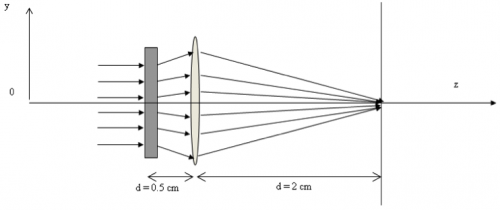

In the two-lens system shown in the figure below, the rectangle on the left represents an unspecified lens L1 of focal length $ f_1 $ separated by 0.5 cm from another lens L2 with focal length $ f_2 $ of 1 cm.

Find the value of $ f_1 $ such that all the rays incident parallel on this system will be focused at the observation plane, located at a distance d of 2 cm away from L2.

Lab exercises

Welcome to the '309 Lab. Before you get started, take a little time to learn your way around. This page gives an overview of all the wonderful resources in the lab.

Lab exercise 1: measure focal length of lenses

Measure the focal length of the four lenses marked A, B, C, and D located near the lens measuring station.

Lab exercise 2: imaging with a lens

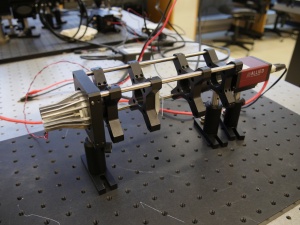

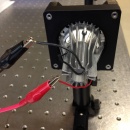

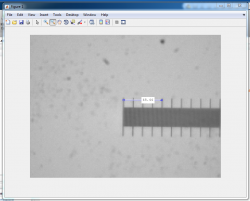

Figure 1 is a picture of the thing you are about to build. From left to right, the apparatus includes an illuminator, an object (a glass slide with a precision microruler pattern on it), an imaging lens, and a camera to capture images. All of the components are mounted in an optical cage made out of cage rods and cage plates. The cage plates are held up by optical posts inserted into post holders that are mounted on an optical table. You will be able to adjust the positions of the object and lens by sliding them along the cage rods.

Gather materials

You can spend a huge amount of time walking around the lab just getting things in the lab, so it makes sense to grab as many parts as possible in one trip. Figure 1 should give you some idea of what the parts look like.

The materials lists below include part numbers and descriptive names of all the components. It is likely that you will find some of the terms not-all-that-self-explanatory. Most of the parts are manufactured by a company called ThorLabs. If you have a question about any of the components, the ThorLabs website can be very helpful. For example, if the procedure calls for an SPW602 spanner wrench and you have no idea what such a thing might look like, try googling the term: "thorlabs SPW602". You will find your virtual self just a click or two away from a handsome photo and detailed specifications.

Screw sizes are specified as <diameter>-<thread pitch> x <length> <type>. The diameter specification is confusing. Diameters ¼" and larger are measured in fractional inches, whereas diameters smaller than ¼" are expressed as an integer number that is defined in the Unified Thread Standard. The thread pitch is measured in threads per inch, and the length of the screw is also measured in fractional inch units. So an example screw specification is: ¼-20 x 3/4. Watch this video to see how to use a screw gauge to measure screws. (There is a white, plastic screw gauge located near the screw bins.) The type tells you what kind of head the screw has on it. We mostly use stainless steel socket head cap screws (SHCS) and set screws. If you are unfamiliar with screw types, take a look at the main screw page on the McMaster-Carr website. Notice the useful about ... links on the left side of the page. Click these links for more information about screw sizes and attributes. This link will take you to an awesome chart of SHCS sizes.

| Optomechanics | Screws and Posts |

|---|---|

|

located in plastic bins on top of the center parts cabinet:

located on the counter above the west drawers:

|

located on top of the west parts cabinet:

|

| Optics | Other |

|

located in the west drawers:

located on top of the east cabinet

|

|

Most of the tools you will need are located in the drawers next to your lab station. Hex keys (also called Allen wrenches) are used to operate SHCSs. Some hex keys have a flat end and others have a ball on the end, called balldrivers. The ball makes it possible to use the driver at an angle to the screw axis, which is very useful in tight spaces. You can get things tighter (and tight things looser) with a flat driver. Here is a list of the tools you will need:

- 1 x 3/16 hex balldriver for 1/4-20 cap screws

- 1 x 9/64 hex balldriver

- 1 x 0.050" hex balldriver for 4-40 set screws (tiny)

- 1 x SPW602 spanner wrench

You will also need to use an adjustable spanner wrench. The adjustable spanner resides at the lens cleaning station. There are only one or two of these in the lab. It is likely that one of your classmates neglected to return it to the proper place. This situation can frequently be remedied by yelling, "who has the adjustable spanner wrench?" at the top of your lungs. Try not to use any expletives. And please return the adjustable spanner wrench to the lens cleaning station when you are done.

- 1 x SPW801 adjustable spanner wrench

Things that should already be (and stay at) your lab station

- 1 x Manta CCD camera

- 1 x Calrad 45-601 power adapter for CCD

- 1 x ethernet cable connected to the lab station computer

Build the apparatus

Use the image of the apparatus to think about how to put your system together. The following guidelines should help get you started. If at any point you have questions, do not hesitate to ask an instructor for help.

Visualize, capture, and save images in Matlab

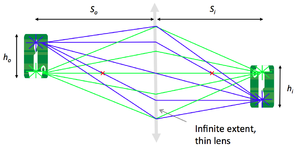

Now that you've learned the basics of mounting, aligning and adjusting optical components, you will through this lab exercise

- Verify the lens maker and the magnification formulae:

- $ {1 \over S_o} + {1 \over S_i} = {1 \over f} $

- $ M = {h_i \over h_o} = {S_i \over S_o} $

- Become familiar with image acquisition and distance measurement using the Matlab software.

Examine images in Matlab

Plot and discuss your results

- Repeat these measurements of $ S_o $, $ S_i $, $ h_o $, and $ h_i $ for several values of $ S_o $.

- Plot $ {1 \over S_i} $ as a function of $ {1 \over f} - {1 \over S_o} $.

- Plot $ {h_i \over h_o} $ as a function of $ {S_i \over S_o} $.

- What sources of error affect your measurements?

- Given the sources of error, how far off could your measurements of magnification be?

Don't take your apparatus apart just yet. You will use it in the next section.

Lab exercise 3: noise in images

Almost all measurements of the physical world suffer from some kind of noise. Capturing an image involves measuring light intensity at numerous locations in space. The Manta G-032 CCD cameras in the lab measure about 320,000 unique locations for each image. Every one of those measurements is subject to noise. In this part of the lab, you will quantify the random noise in images made with the Manta cameras, which are the same ones that you will use in the microscopy lab.

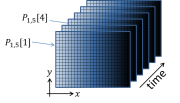

So what is noise in an image? Imagine that you pointed a camera at a perfectly static scene — nothing at all is changing. Then you made a movie of, say, 100 frames without moving the camera or anything in the scene or changing the lighting at all. In this ideal scenario, you might expect that every frame of the movie would be exactly the same as all the others. Figure 2 depicts dataset generated by this thought experiment as a mathematical function $ P_{x,y}[t] $. If there is no noise at all, the numerical value of each pixel in all 100 of the images would be the same in every frame:

- $ P_{x,y}[t]=P_{x,y}[0] $,

where $ P_{x,y}[t] $ is the the pixel value reported by the camera of at pixel$ x,y $ in the frame that was captured at time $ t $. The square braces indicated that $ P_{x,y} $ is a discrete-time function. It is only defined at certain values of time $ t=n\tau $, where $ n $ is the frame number and $ \tau $ is the interval between frame captures. $ \tau $ is equal to the inverse of the frame rate, which is the frequency at which the images were captured.

You probably can guess that IRL, the frames will not be perfectly identical. We will talk in class about why this is so. For now, let's just measure the phenomenon and see what we get. A good way to make the measurement is to go ahead and actually do our thought experiment: make a 100 frame movie of a static scene and then see how much each pixel varies over the course of the movie. Any variation in a particular pixel's value over time must be caused by random noise of one kind or another. Simple enough.

(An alternate way to do this experiment would be to simultaneously capture the same image in 100 identical, parallel universes. This will obviously reduce the time needed to acquire the data. You are welcome to use this alternative approach in the lab.)

We need a quantitative measure of noise. Variance is a good, simple metric that specifies exactly how unsteady a quantity is, so let's use that. In case it's been a while, variance is defined as $ \operatorname{Var}(P)=\mathbf{E}\left((P-\bar{P})^2\right) $.

So here's the plan:

- Point your camera at a static scene that has a range of light intensities from bright to dark.

- Make a movie.

- Compute the variance of each pixel over time.

- Make a scatter plot of each pixel's variance on the vertical axis versus its mean value on the horizontal axis, as shown in Figure Figure 3.

Plotting the data this way will reveal whether or not the quantity of noise depends on intensity. With zero noise, the plot would be a horizontal line on the axis. But you know that's not going to happen. How do you think the plot will look?

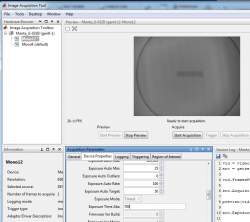

Set up the scene and adjust the exposure time

You can make the measurement with the same setup you put together for the previous lab exercise. Follow the detailed procedure below:

- Set up the scene.

- Slide the lens as close to the camera as it gets.

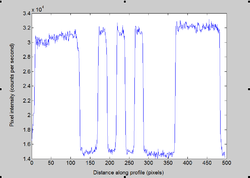

- Slide the microruler slide to produce an in-focus image.

- Use the CURRENT knob on the power supply to set the LED current to 0.2 A. Make sure you have an ND filter in your illuminator.

- In the Device Properties tab, set the Exposure Time Abs property to 100.

- Check the exposure.

- Press the Start Acquisition button in the Acquire pane of the Preview window.

- Press the Export Data... button.

- Select MATLAB Workspace in the Data Destination popup menu and type exposureTest in the Variable Name edit box.

- Switch to the MATLAB console window. (Press alt-tab until the console appears.)

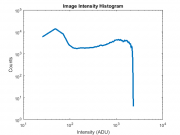

- Plot a histogram of your data on log-log axes (use the MATLAB code below).

- Use your histogram to obtain the correct exposure and current settings.

- Your histogram should show a reasonably uniform distribution of pixel values between about 10 and 2000. Figure 4 shows a reasonably nice histogram.

- If necessary, change your camera exposure or LED current setting to get a good distribution of values.

MATLAB code for plotting a histogram:

[ counts, bins ] = hist( double( squeeze( exposureTest(:) ) ), 100); loglog( bins, counts ) loglog( bins, counts, 'LineWidth', 3 ) xlabel( 'Intensity (ADU)' ) ylabel( 'Counts' ) title( 'Image Intensity Histogram' )

Acquire movie and plot results

Once you are set up correctly, make a movie and plot the results using the procedure below:

- Capture a 100 frame movie.

- Go to the General tab of the Acquisition Parameters pane and change the Frames per trigger property from 1 to 100.

- Press Start Acquisition.

- Press the Export Data... button.

- Select MATLAB Workspace in the Data Destination popup menu and type noiseMovie in the Variable Name edit box.

- Plot pixel variance versus mean.

- Switch to the MATLAB console window. (Press alt-tab until the console appears.)

- Use the code below to make your plot.

pixelMean = mean( double( squeeze( noiseMovie) ), 3 ); pixelVariance = var( double( squeeze( noiseMovie) ), 0, 3 ); [ counts, binValues, binIndexes ] = histcounts( pixelMean(:), 250 ); [counts, binValues, binIndexes ] = histcounts( pixelMean(:), 250 ); binnedVariances = accumarray( binIndexes(:), pixelVariance(:), [], @mean ); binnedMeans = accumarray( binIndexes(:), pixelMean(:), [], @mean ); loglog( pixelMean(:), pixelVariance(:), 'x' ); hold on loglog( binnedMeans, binnedVariances, 'LineWidth', 3 ) xlabel( 'Mean (ADU)' ) ylabel( 'Variance (ADU^2)') title( 'Image Noise Versus Intensity' )

Questions

- Did the plot look the way you expected?

- How does noise vary as a function of light intensity?

- Include the plot in your writeup.